The Elizabeth River Project acknowledges the Indigenous peoples of Tsenacommacah (Seh-nuh-cuh-MAH-kah), which means “land of many villages” and is the coastal Algonquian name for Eastern Virginia. We thank the Nansemond, Chesepioc, and other Indigenous nations of the Powhatan Confederacy for continuing to steward these lands and waters as they have for thousands of generations.

We honor them now and in the future as the original knowledge-keepers of just relationship with the river that together we seek to heal.

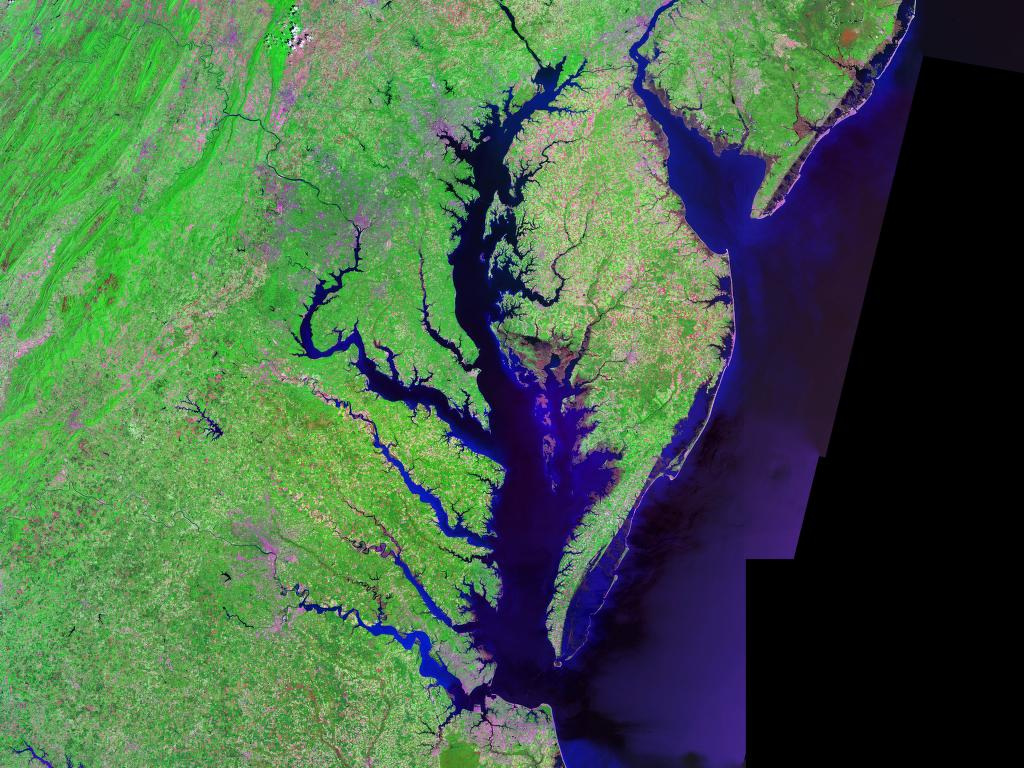

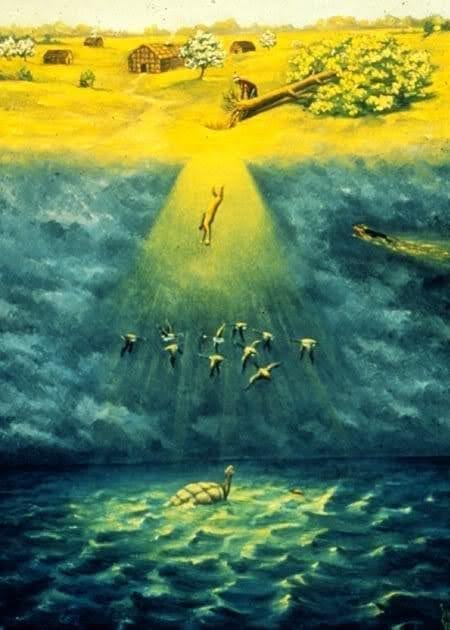

From outer space, the waters of Chesapeake Bay appear as a writhing many-legged serpent stamped upon the eastern shoreline and rearing its head for some two-hundred miles up into the North American continent, or what Indigenous peoples often refer to as “Turtle Island.” Roughly 150 rivers and streams empty out into the Chesapeake as the continent perpetually sheds its waters out through this largest of American estuaries. Positioned at the very mouth of the Bay is the Elizabeth River and, as such, all the waters of the Chesapeake watershed cycle through her, making of this a rich and abundant land base, saturated with marine life and other natural resources. And for thousands of years the Indigenous peoples living here built along these shores and found their livelihoods in all that the river at the foot of the Bay has to offer.

The name “Turtle Island” comes from the Indigenous belief that the continent was originally formed on the back of a turtle in order to create a resting place for Sky Woman, who had fallen from an upper-world down to this place we inhabit below. In this distant time, the world was yet all one sea. Rather than allowing this woman from the sky to be dashed upon the waves, a flock of geese consented to arrest her fall, couching her within their feathery wings and safely lowering her to the surface. The great turtle then rose from the waters to offer her a place of repose and soon other sea creatures—creatures familiar to the Elizabeth River system such as the otter, the duck, and the muskrat—all endeavored to plumb the watery depths in an attempt to secure earth from the bottom, in order to make a place for the Sky Woman to live. It was the lowly muskrat, in the end, who alone was able to dive deep enough to complete the task. When the muskrat’s offering was spread across the turtle’s back, the surface began to grow and this became the earth upon which we all live, work, and sustain ourselves today.

Rejoicing over her new home, the Sky Woman performed a dance, sprinkling seeds, retained from the above-world, into the newly formed surface of the earth, and from this were sprung plants and trees. This Indigenous story of the creation of Turtle Island is told in many different ways by many different Indigenous peoples for whom it forms a core belief about our relationship with the world and how it was made in collaboration with other than human-beings—beings like the otter, the turtle, the geese, the muskrat. Sky Woman’s dance was a kind of ceremony meant to honor and bind this relationship so later generations would not forget. When we take a step back to view images of the whole North American continent from space, we can perhaps even begin, ourselves, to see the turtle’s form.

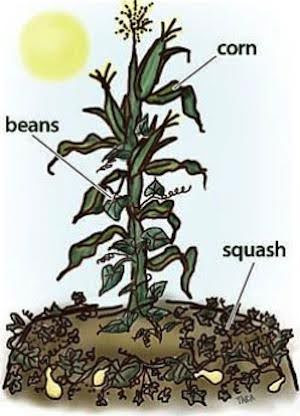

Indigenous peoples living within the watershed of what we today call the Elizabeth River, understood this relationship and helped to cultivate it over many thousands of years. All the Indigenous communities of present-day Eastern Virginia, including the seven federally recognized tribes of the Nansemond, Pamunkey, Rappahannock, Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, and Monacan peoples and the state recognized tribes of the Mattaponi, Nottoway, Cheroenhaka, and Patawomek, were established along the major Virginia waterways. Their traditional practices of cultivating crops such as corn, beans, and squash, hunting and fishing, and harvesting other resources such as fruits, berries, tobacco, and medicinal herbs, were performed in such a manner as to maintain balance with the ecosystem that sustained them. While, today, some might trivialize such practices as being “at one with nature,” or even “primitive,” they were, in fact, founded in intricate and intentional strategies for survival, developed over millennia of having existed within this particular ecosphere. European immigrants, on the other hand, have only been here for a comparatively short time, but have managed to off-set the carefully maintained balance of the Indigenous inhabitants, exhausting the soil, polluting the air and waters, and weakening the overall resilience of the watershed, in ways that throw us into crisis and threaten the continued existence of everyone on Turtle Island. The Elizabeth River Project was, in fact, created in response to this ongoing crisis.

The land along the Elizabeth River, and across much of south-eastern Virginia, was (and still is) known to the Natives who live here as Tsenacommacah which, in the Eastern-Algonquian dialect spoken by the inhabitants, can be translated as meaning “land of many villages.” Villages along the river consisted of roughly 100 members each, with houses constructed from bent-over saplings, bound by bark and reed, and covered with sturdy matts made of marsh grasses. Some of these structures, especially those used for ceremonial gatherings, were large enough to fit over a hundred people, but most were built to accommodate smaller family units. The kinship networks of extended families and clans formed the structural glue of this village world, and tribal communities travelled and gathered often whether for pleasure, ceremonial purposes, or seasonal subsistence.

Indigenous maintenance of the land was performed collectively by each tribal community. Although women largely managed the planting, while men hunted and fished, labor was shared depending on the season and the need. Women cultivators developed a symbiotic system of growing corn, beans, and squash, referred to today as Three Sisters agriculture. Although not Native to the Tidewater, these crops were successfully adapted to the soil and climate. The seeds for the corn and beans were placed in regularly-spaced mounds, allowing them to grow together, while the squash seeds were laid around the perimeter of each mound. Planting in this way allowed for a relationship in which the beans released nitrogen into the soil, adding essential nutrients for the crops to grow. The corn stalks served as poles for the beans to climb around, and the broad leaves of the squash plant shaded the area around the corn stalks, reducing the number of weeds, while the squash blossoms produced a scent that repelled insects and other pests. All told, it is a system that, while requiring steady care, was much less labor-and-irrigation intensive than European farming practices. Historians and anthropologists have often downplayed the overall productivity of Indigenous cultivation of the land, but the reports of colonists from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries can paint a very different picture. John Smith, writing of his journey up the Nansemond River in 1608, reported seeing “large cornfields, in the midst of a little Isle, and in it was abundance of Corne” (G.H. 352). This was, in fact, a common sight and of great interest to the colonists who depended upon the abundance of Indigenous surplus produce in order to survive. George Percy, another of the original colonists, reported passing through “the goodliest Corne fieldes that ever was seene in any Countrey” (G.H. 927).

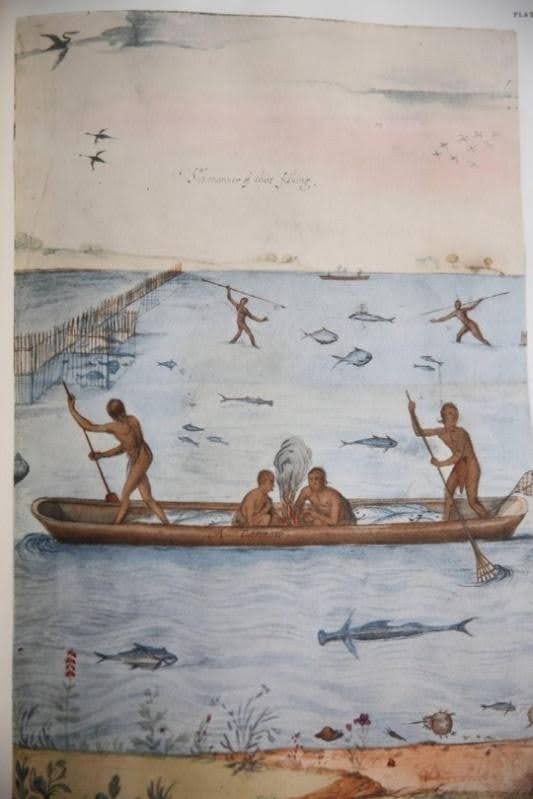

Indigenous peoples of the east coast received the largest portion of their nutrition from the foods they planted, practicing regular crop rotation and even the relocation of their villages, roughly every seven years, to maintain the vigor of the soil. But hunting, fishing, and the cultivation of shellfish were also important additions. Deer, bear, turkey, and waterfowl were all a staple of Indigenous diets. The Elizabeth River would have been crossed with fishing weirs to facilitate the harvesting of fish and crabs in season and the oyster banks were encouraged and left to grow, as they not only supplied sustenance, but helped to stabilize the shoreline and filter the water to keep it fully oxygenated, which contributed to the overall resilience of the landscape. Indigenous communities also maintained fruit-bearing orchards and vast fields of berries. The settlers, themselves, feasted on the rich strawberry fields of what is today Hampton Roads, imagining that the fruit simply grew there wild.

The land along the Elizabeth River, and across much of south-eastern Virginia, was (and still is) known to the Natives who live here as Tsenacommacah which, in the Eastern-Algonquian dialect spoken by the inhabitants, can be translated as meaning “land of many villages.” Villages along the river consisted of roughly 100 members each, with houses constructed from bent-over saplings, bound by bark and reed, and covered with sturdy matts made of marsh grasses. Some of these structures, especially those used for ceremonial gatherings, were large enough to fit over a hundred people, but most were built to accommodate smaller family units. The kinship networks of extended families and clans formed the political glue of this village world, and tribal communities travelled and gathered often whether for pleasure, ceremonial purposes, or seasonal subsistence.

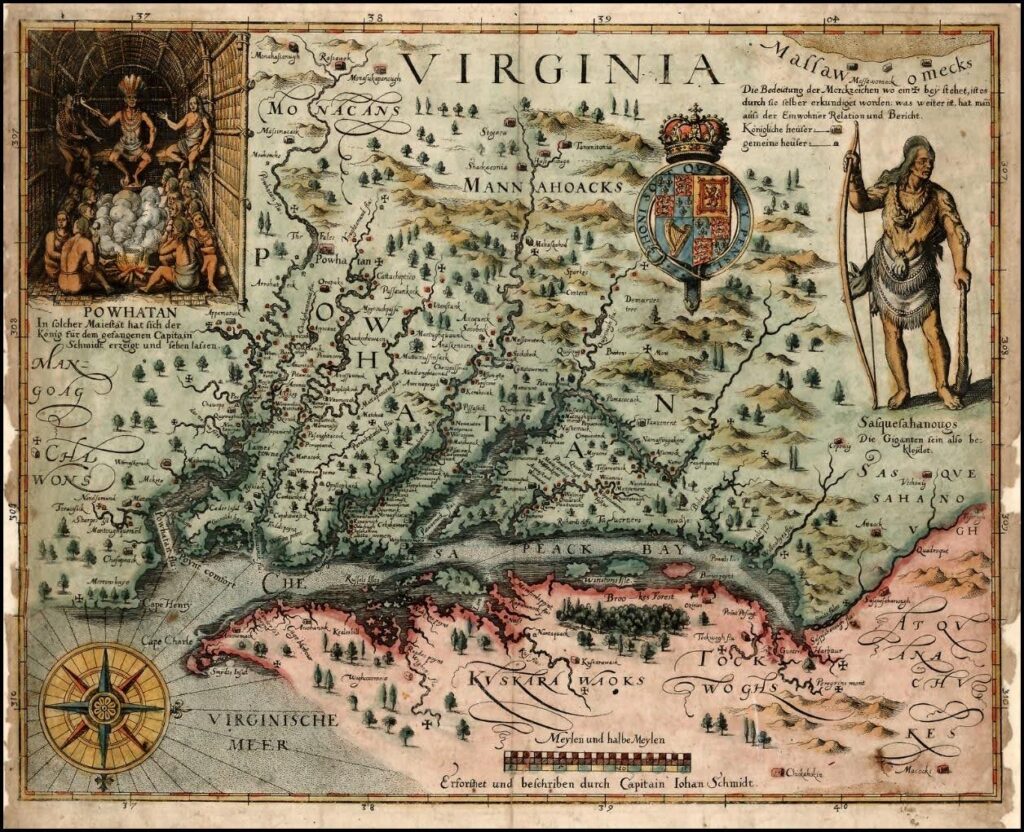

But the colonists, despite their own hyperbole concerning the “emptiness” of the land, were well aware of the tribal people positioned along the riverways and they encountered them, whether for trade, counsel, or conflict, on an almost daily basis. When we view the map of Virginia made by John Smith and published upon his return to England in 1612, we see villages planted along every stretch of waterway, with only the precarious little settlement of Jamestown standing in for English occupied territory. Smith’s map, on its own, bears witness to the accuracy of the Indigenous name, Tsenacommacah, or land of many villages. In fact, archeological research suggests that, in 1607 when the first permanent English settlers arrived, upwards of 20,000 people inhabited this region.

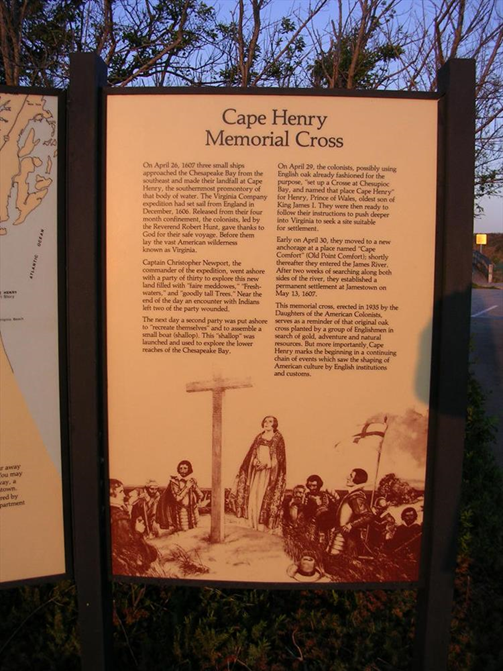

Smith’s mapping of Virginia served another vital settler-colonial function by giving name to much of the landscape. An interesting project is to closely examine his map, which is astoundingly accurate given the primitive tools at his disposal and the speed with which he made it, and determine which features have retained their Algonquian names and which have been Anglicized. The Cheseapeack Bay (as Smith spelled it), for instance, has kept its Indigenous title over the years (the meaning of the word “Chesapeake” has been lost—but it may be Algonquian for “town beside the water”), but the land of Tsenacommacah itself had already been rechristened “Virginia” by the settlers, erroneously implying “virgin-land,” but equally erroneously evoking the ‘Virgin-Queen” of England. A closer look reveals that the James River, as we know it today, was still called the “Powhatan River” in Smith’s time, after the principal tribe of the region. Cape Henry and Cape Charles stood sentinel over the entry of the Bay, but places such as Accomack and Nandsemond were never renamed by the English. Although Kekoughtan is not listed on Smith’s map, this Native village, which first hosted the colonists on their arrival in May of 1607, retained its name up until the first meeting of the House of Burgesses in 1619, when its two English representatives announced “they will be pleased to change the savage name . . . and give the incorporation a new name” (H.O.B. 1619: July 30). That new name would be Elizabeth City, which initially encompassed much of modern-day Hampton Roads, including both Hampton and Norfolk.

The colony, in its earliest days, was poorly provisioned and marred by jealousies and infighting among its leaders. The principal function of the colony was to extract resources from the land, be it gold, silver, silk, lumber or, as was ultimately the case, tobacco, that would make a return on the investment of the English-based Virginia Company. The colonists were instructed by their sponsors to maintain peaceful relations with the “Naturales,” however their very presence proved a provocation. Although they were at first greeted with astonishing hospitality by the Indigenous peoples all along the Powhatan [now James] river system, finding themselves courted and fed, the colonists quickly began to wear out their welcome. As was true of every English settlement to follow, the Jamestown colony depended on Indigenous agriculture to survive, and when the local Natives no longer found it practical to trade corn in return for trinkets, the settlers resorted to force to acquire what they needed.

Despite a milieu of shocking violence, deprivation, cruelty to themselves and others, and even well-documented cases of cannibalism at Jamestown, the colony managed to hang on. Its objective was ever to wrest complete control of the land and render the Indigenous peoples who lived there vassals of the English crown and church. From the start, monies were put aside by the Virginia Company to form a school for Native children, with the aim to educate them in the Christian faith. While this might, perhaps, be regarded as benevolent in its intention, the consent of the Native community was not regarded as necessary. European settlers viewed Indigenous civilization as inferior to their own, and were dismissive of what they deemed “savage” and even “hellish” practices. A common refrain was that Native peoples had no form of government, law, or religion. But lurking close behind these highly self-serving viewpoints was a very common variety of acquisitiveness and greed. The dehumanization of Indigenous peoples helped to facilitate imperialistic desires and, despite attempts by the Powhatan confederacy to resist colonial encroachment, the various nations of the Nansemond, Pamunkey, Chickahominy, Rappahannock, Mattaponi, Monacan and others were ultimately broken up and driven from their lands. By 1619, enslaved labor was introduced to the colony and Indigenous people were often, themselves, caught in this system of human trafficking and exploitation.

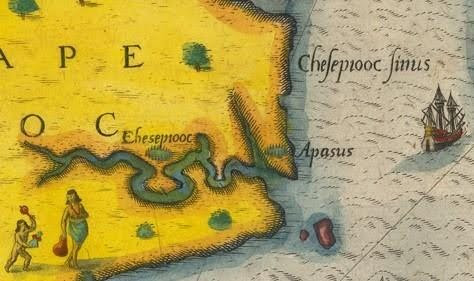

An additional look at John Smith’s 1612 map reveals that the Elizabeth River itself was yet to be dignified with a name. Documentary evidence, however, suggests that the river was known as the Chesepiooc, as first indicated in a 1585 painting by the Roanoke colonist John White, or Chesepayacke, as it is referred to in a 1629 report of the Virginia House of Burgesses. John Smith, too, marks the village of the Chesepeack on his 1612 map. He first turned his attention to the river in 1608, as he made his way home from his mapping expedition of the Chesapeake Bay. In his 1624 General Historie of Virginia, he recalled,

We sayled up a narrow river up the county of Chisapeack; it hath a good channell, but many shoules about the entrance. By that we had sayled six or seaven myles, we saw two or three little garden plots with their houses, the shores overgrown with the greatest Pyne and Firre trees wee ever saw in the Country. But not seeing or hearing any people, and the river very narrow, we returned to the great river [the Powhatan River] to see if we could find any of them. (J.S. 351-352)

This is the first documented description of the interior of what is today known as the Elizabeth River.

An accurate understanding of the dynamics of colonization at Jamestown can be garnered from Smith’s account of what directly followed. Failing to meet any Indigenous people on the Elizabeth River, Smith next “discovered the river of Nansemond” (J.S. 28). Smith wrote in his General Historie that his habitual practice when dealing with local Indigenous peoples on first meeting, was to “demand their bowes and arrows, swords, mantels and furrs, with some childe or two held hostage, whereby we could quickly perceive, when they intended any villany.” In other words, he would take Native children hostage in order to extort from unexpecting villagers a certain quantity of corn and provisions to support the starving colonists at Jamestown. He wrote how such tactics were used to “purchase peace” and curb their “insolencies” (J.S. 340). But regardless of whatever gloss he places upon his actions, these were nothing less than bald acts of terrorism and piracy.

When Smith caught sight of the abundant corn fields along the Nansemond River in 1608, he quickly attempted to put these aforementioned strategies into action. But by this point the Nansemond (and the Chesipeack) had been warned of Smith’s tactics and combined to thwart him. They evacuated their villages of women and children and attempted at first to drive Smith and his men off peacefully. When Smith refused to leave, they followed him upriver in their canoes, a hundred warriors or more, and finally opened fire. In the contest that followed, Smith and his men debated whether “it were better to burne all in the Isle, or draw them to composition, till we were provided to take all they had, which was sufficient to feed all our Colony.” These were the options they considered, “but to burne the Isle at night it was concluded” (J.S. 353). In other words, because it was deemed too risky to challenge the Nansemond head on, Smith and his men determined instead to punish them by burning down the village, which was the spiritual center of the Nansemond community, home of their chief or werowance, and where they stored their most sacred relics.

Somehow the Nansemond managed to prevent this complete disaster from occurring and negotiated that, when Smith next returned, they would supply him with four hundred bushels of their own corn. This is how “peaceful” relations were maintained by the Jamestown colonists. The Nansemond, for all their troubles, were labeled “a proud and warlike Nation” by Smith, but this was no compliment. It was a signal to later colonists that the Nansemond must be dealt with forcibly, using terror tactics similar to those he had used. In the following year, a campaign was sent to finish what Smith had threatened. When the “promised” corn was not provided, the settlers burned down the principal village of the Nansemond people, destroying everything and everyone in their path, murdering the Nansemond leaders.

As for the Elizabeth River, it remains unclear when this name finally took hold. The first recorded mention of it can be found in the records of the Virginia Company for July 12, 1620. A settler, John Wood, who was licensed by the Company to begin a lumber concern for ship-building, petitioned the Company that they trade his eight shares of land on the Hampton side of Elizabeth City (formerly Kekoughtan), for “8 shares on Elizabeth River . . . because theron is Timber fittinge for his turne, and water sufficient to Launch such Ships as shalbe ther built for the use and service of the Company” (V.C. 402). Despite Wood’s referencing of the river as “Elizabeth,” reports from the Virginia House of Burgesses continued to refer to the river as the Chesipiack for decades to come.

The Native people of Virginia did not die off or disappear. With a tenacity greater than that of the early Jamestown colonists, they hung on and persevered, despite some four-hundred years of persistent warfare, persecution, and neglect. The Nansemond and the Chesipeoc are the peoples properly Indigenous to the lands making up the Elizabeth River watershed. Although the Chesipeoc tribe is no longer extant, their families likely merged in colonial times with those of the Nansemond. In the Algonquian language the word Nansemond means “fishing point” and the Nansemond Indian Nation is still situated along the river system where they have fished and received their sustenance for thousands of years. They received state recognition in 1985 and in 2018 they became a federally recognized Indian tribe.

The tribal headquarters for the Nansemond are located on the site of their historic Mattanock Town, which can be seen on Smith’s 1612 map. In May of 2024, seventy-one acres of riverine lands encompassing this ancestral site were yielded back to the Nansemond tribe by the town of Suffolk. As a result, in August of 2024, the Nansemond were able to hold their annual powwow on grounds that were, for the first time in some 400 years, indisputably their own. Nansemond Chief, Keith Anderson, was also present at the opening consecration of the Elizabeth River Project’s Ryan Resiliency Lab in June of 2024, where, in full and imposing regalia, he sprinkled tobacco around the site of the lab and offered the blessing of the tribe. Today the Nansemond Indian Nation is fully committed to building the resilience of the lands that stand between the Elizabeth and Nansemond Rivers. They have launched initiatives to rebuild the great oyster beds that Smith first reported on when sailing up the river in 1608, and to reforest lands alongside the river with trees that will help build and strengthen the shoreline. They have also begun a unique venture for an Indigenous tribe, of opening up Fishing Point Healthcare Services, a number of state-of-the-art healthcare facilities throughout Hampton Roads that effectively connects the resilience of the land with the resilience and health of all its inhabitants. In these ways, the Nansemond Indian Nation continues to act as a faithful steward of the ancestral lands they have for so long inhabited along the river that bears their name.

https://www.umasspress.com/9781625342591/through-an-indians-looking-glass/

Notifications